How economics is failing us

The following text is an edited version of a public address given by Professor Bill Mitchell at University House in Newcastle on October 4, 2000. It was part of the University of Newcastle Professorial Lecture series.

Objectives of Lecture

Introduction

At the outset we should be reminded of a treaty which the Australian Government is a signatory - the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights September 24 1948. A relevant clause is as follows:

Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

I consider our economy to be facing four major problems:

- Persistently high unemployment.

- Rising economic inequality.

- Increasing environmental degradation.

- The future of work.

I plan to focus more on unemployment and inequality in this lecture. In terms of environmental degradation, there is a need to change the composition of output. My argument is not about anti-growth. We need growth to maintain living standards but we need to change the mix of activities that we currently are involved in. There are a range of activities that will not be compatible with sustainable growth. Equally, there are a number of jobs that could be done to improve environmental conditions. The type of jobs that are needed to do this will never be provided by the private sector because they would produce outputs, which would be environmentally productive but would not deliver satisfactory private profit outcomes. In these cases, public sector involvement is required.

This prima facie rationale for public sector involvement is magnified when we consider the future of work. At present we consider work in terms of gainful work whereby someone must be prepared to pay you to do something. However, it is conjectured that technological advances will reduce the number of production workers in the future. If work remains an important dimension of one's self image and self esteem, then we are going to have to implement creative ways to occupy people as conventional job opportunities decline. In other words, we are going to have to broaden the definition of useful work. Again, it can be argued that the public sector - as an employer - will be crucial in this process.

Boats on the tide

It used to be argued by Arthur Okun and others that all boats rise on a high tide. This justified their position that it was important for governments to maintain the economy at high-pressure through the use of fiscal and monetary policy. Considerable research has been undertaken in the USA connecting economic growth, job creation, employment quality, and earnings distributions. At question is whether a high growth economy can deliver quality jobs and benefits across the community. Okun argued that growth brought productivity improvements, increasing labour force participation rates, occupational upgrading, and rising average earnings for the most disadvantaged in the labour market. Rates of poverty declined and there was a narrowing of the earnings distribution.

Most OECD economies experienced these benefits in the post-War period. However, since the 1970s, growth no longer seems to be associated with improved equity in a number of countries. In America, despite a sustained growth period, the earnings and income distributions became increasingly unequal from the 1980s to the mid 1990s with real wages falling or stagnant for the lower quintiles of the distribution.

In Australia adult earnings inequality has increased since the 1970s, with the rise over 1986-1996 driven largely by downgrading of the lower half of the full-time wage distribution. Ann Harding has argued that from 1982-94, tax and transfers offset the growing market-based inequality.

The Australian economy has undergone considerable restructuring with policies encouraging labour market deregulation, microeconomic reform and international competitiveness since the late 1980s. Some argue that the rising inequality has been exacerbated by the restructuring. The link between growth, productivity and job generation is changing as is the type and quality of jobs being created. There are now a variety of non-standard employment arrangements with less earnings security.

So we know that economic growth per se does not provide improving circumstances for the disadvantaged. The economy now operates such that the well-off can expropriate increasing shares of the wealth produced for themselves at the expense of the less well-off. This is duplicated when we consider the global economy. Rich economies are getting richer by creating increasing disadvantage and poverty in the poorer countries.

The following graph shows the rising inequality in terms of Percentage Share of Gross Weekly Income by Quintiles. Other inequality measures are consistent with this trend.

In the past, poverty was largely a function of age and not being in the labour force (that is, working in that context because unemployment was so low). Now, the highest proportion of those who are poor (less than 50 per cent of median income) are of working age and in the labour force. That is, they are either unemployed or on low-pay (probably working part-time because of a lack of full-time employment). The following graph provides pictorial evidence of this.

Unemployment and Inflation

The next graph, depicts the relationship between the inflation rate and the unemployment rate for the period 1961 to 2000.

The rise in the unemployment rate and inflation rate occurred around the same time as the first OPEC oil shock in the mid-1970s. The pattern was replicated in most OECD economies. This was the first time that western economies had experienced stagflation - the coincidence of high inflation and high unemployment. It was at this time that the mania about budget deficits - that budgets should balance - began to influence the conduct of fiscal policy. Since then unemployment has never returned to the levels established in the 1960s. The question is why? Australia had the strongest employment growth in the OECD during the second half of the 1980s, yet unemployment also remained high.

Unemployment rates in almost all OECD economies have persisted at higher levels since the first OPEC shocks in the 1970s. Several writers have targeted institutional arrangements in the labour market (wage setting mechanisms and trade unions) and government welfare policies encouraging people to engage in inefficient search as the cause (for example, OECD Jobs Study, 1994). We suggest that the persistently high unemployment over the last two decades lies in an unwillingness of policy makers to use fiscal and monetary policy in an appropriate manner. The rapid inflation of the mid-1970s left an indelible impression on policy makers, who became captive of the resurgent new labour economics and its macroeconomic counterpart, monetarism. The traditional practice of aggregate demand management and fine-tuning was abandoned as governments adopted "inflation first" strategies. The result has been that GDP growth in OECD countries over the last 20 years or more has generally being below that required to absorb the labour force growth and the growth in labour productivity. This is the principle reason for the persistently high unemployment.

The abandonment of full employment by governments in the 1970s has been exacerbated by the urgency of deregulation and welfare cutbacks in the 1980s and beyond. This "supply-side" approach is exemplified in the OECD (1994). Central Banks now appear to be dominated by the pursuit of low inflation and a reliance on the market system to return economies to full employment, but this has yet to occur.

My contention is that the clue to the persistently high unemployment lay in the withdrawal of the public sector from its direct role in the labour market as an employer and in the manner in which they pursued inflation-first policy strategies.

Precarious Employment

Not only has unemployment remained high, but the quality of employment has deteriorated. We now talk about the rise in precarious employment, which alludes to the fact that work tenures are now insecure and that a rising proportion of employment on offer is fractional, low-paid work. Since 1978, there have been around 2.9 million jobs created of which around 50 per cent have been part-time. In that time, the labour force has grown by 3.0 million. The unemployment-vacancy ratio clearly indicates that there has been a persistent demand constraint imposed on the labour market. The rise in importance of part-time work has often been interpreted as a reaction to the desire by workers for more flexible work arrangements. Over the period, the number of part-time workers wanting longer hours has more than doubled which indicates that the demand constraint and structural changes towards part-time work have been forced upon the work force. This is reinforced by the steady percentage of unemployed workers who desire full-time work. There is also a considerable number of hidden unemployed. The following tables summarises the changes in fractional employment between 1978 and 1999.

The decline of public employment

A marked fact about the labour market in Australia over the last 25 years or so is the withdrawal of the public sector as an employer. The next table summarises the sectoral employment aggregates between 1967 and 1999. The results are striking. In 1967, the unemployment rate was a low 1.93 per cent. In the first quarter of 2000, the unemployment rate now hovers between 6.5 and 7 per cent. What has happened over this period? What has been the growth in the labour force? What has been the growth in employment? What has been the growth in the constituent parts of employment (Private and Public)? The following discussion examines these trends and sources the reason why the unemployment rate has trebled.

According the Australian Bureau of Statistics data, private business employment grew by 2.18 per cent per annum between June 1967 and September 1999. In the same time, the civilian labour force grew by 2.12 per cent per annum. The result is that the ratio of private employment to the labour force (the private employment rate) fell from 78.5 per cent to 77.1 per cent. Overall government employment over the same period has failed to keep pace with the rising labour force. Following the mass privatisations since 1990, employment in public enterprises has plummeted from to 442 thousand to 198.6 thousand (a large part of that is privatised employment). So the private business figures include jobs that were formerly in the private sector. However, the growth in private employment has not been sufficient to offset the public sector losses. Over the period, General Government employment went from 631.2 thousand to 1248.9 thousand, roughly proportional with labour force growth. Unemployment rose from 92.5 thousand (1.93 per cent) to 682.6 thousand (7.2 per cent).

The evidence is that despite the claims that the private sector would absorb workers released from the public sector after the severe cutbacks the reality is different. The private sector has always only been able to employ around 77 per cent of the labour force. Unless the public sector provides jobs for the remaining workers seeking employment, unemployment will remain high. The Job Guarantee to be examined in a later section is designed to ensure that the public sector meets the slack that the private sector generates.

An additional warning in interpreting the data in the Table is necessary. While the privatesector has maintained employment growth in proportion to the labour force growth the ratio of full-time to part-time employment haschanged dramatically. In 1978, full-time jobs accounted for around 85 per cent of the total, whereas by November 1999, the ratio was down to 74 per cent. It is true that some of this change reflects the preferences of the workforce for casual arrangements. But ABS data shows that over that time, the percentag of part-time workers who wanted to work more hours had doubled (now at around 29 per cent).

Another way of viewing the high unemployment is to consider the relationship between the labour force and employment over the same period. The following graph shows clearly that once the public sector bailed out of its responsibility of employment, the labour force and employment series have diverged. The private sector was unable to pick up the jobs growth. following the massive withdrawal from the economy by the government.

An historical view

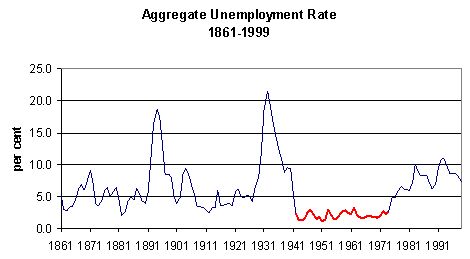

How has this occurred? To appreciate the impact of the public sector on unemployment we need to take a longer perspective. In fact, the period of low unemployment (and falling inequality) from 1950-1974 was rather short in historical terms. By piecing together historical data from a number of sources the following graph was constructed.

Prior to Great Depression mass unemployment was considered impossible because price adjustments would eliminate any excess labour supply. The Depression was a major blow for the neoclassical (microeconomic) belief in market processes. It simply did not work. Wages were cut but unemployment worsened. The then major criticisms of the Market (market failure) were overshadowed by the failure of the system to generate enough work. Keynesian economics allowed capitalism as a system to survive the Great Depression. It was discovered that monetary and fiscal policy could be used to fight economic slumps From that period, we had full employment - via public sector policy intervention. The red section highlights this period. From the viewpoint of economic theory, this was the beginning of macroeconomics as a discipline. The graph shows that the periods when Keynesian government policy was not operating (non-red periods), the private market alone has never delivered such low unemployment rates.

In terms of the Post War period to 1975, the reason that we maintained full employment and declining inequality was because the collective will was stronger than the individual will. This required the government to play a key role. Shared values were well defined and allowed the government to act on our behalf to distribute resources more equally. Shared values lead to social cohesion.

Tension in the ranks

There had always been a tension within the economics profession during this period. The tension is characterised by the division between the microeconomists, who stressed The Market, individualism, and passive governments, and the macroeconomists, who stressed regulation, collective will and active government intervention.

There was a curious dichotomy within the profession over the post-WW2 years. Neoclassical economists knew that the real world did not behave like their text book model. For the perfect competition results to hold everything had to be small. No-one or thing could exert influence on the market. You had to have perfect foresight to solve the optimal allocation. There could be no major fixed costs of entry. Even still, the pure model was not without problems - externalities, public goods. Economic theory is an axiomatic system - what you conclude is based on what you assume. But economists all know that the benchmark optimal results depicted in the perfect competitive model is only an abstraction and cannot be applied to the real world where the restrictive conditions for optimality never are to be found. Economists are culpable in this respect as they know there is a sleight of hand operating when economic rationalist policy makers appeal to the models of the economists for authority as they further cut into public welfare spending or privatise a public asset.

To understand the current period where The Market has been raised once more to the pedestal, we should briefly reflect on economic ideology. The development of the major micro propositions occurred in the late C19th when Marxism threatened the property rights of capitalists. Free market models appearing in text books (still today) were designed to exemplify fairness and efficiency. By sleight of hand this abstraction became real world commentary. This is a major area where the mean-spirited economists are culpable.

So it should be stressed that The Market paradigm arose essentially for ideological reasons. The appeals to Adam Smith and other classical economists as the fathers of modern rationalist economists are misplaced. That is the topic of another discussion. It also has to be stressed that the profession controls the paradigm in a number of ways to weed out troublemakers. The tension throughout the growth period simmered. By the late 1960s, the neoclassical resurgence was poised to make an impact. A pretext was required - the OPEC oil shock confounded Keynesian thinking (who had only considered unemployment and inflation in terms of the inflationary gap model. The two could not coincide). This confusion, led through various channels, to the comeback of the previously discredited neoclassical model.

The revered Market

Nothing captures the current period of policy-making more than the statement by Margaret Thatcher that:

There is no such thing as society

The post 1975 period saw a resurgence of belief in:

- The Market as the supreme allocator of resources.

- The individual as the agent of economic activity.

- The pursuit of greed being optimal.

It also saw a decline in support for public sector activity of any dimension. This is the so-called economic rationalist era. Given the total lack of credibility that this approach faced during its failure to solve the Great Depression it is an interesting question as to how its resurgence has been so successful. That is the topic of another discussion.

The dominant paradigm now, once again, exalts the individual and The Market. The more individuals follow their preferences unfettered by government action the better will be the outcomes for all. Governments therefore should not introduce impediments to market outcomes. Spending and taxation policies distort the free market outcomes and reduce the outcomes for all.

One of the interesting things is the lack of concordance of the Market approach with empirical reality. Virtually none of the theoretical propositions that underpin orthodox theory has withstood empirical scrutiny. It is remarkable that these ideas persist and grow when there is virtually no empirical evidence to support any of these propositions.

The other side of this coin is that individuals are then to blame for their outcomes. If they are in unfortunate situations they must be lazy - not willing to work or stay in education, or whatever. Systemic failure is ruled out.

The economic rationalists also apply a Market test of profitability to everything. Accordingly, the Market arbitrates value and survival in the market depends on profits. Shareholders punish poor performance. The problem for public institutions is that they do not have shareholders. Therefore it is clear that we should privatise public assets to meet the test of profitability. Of-course, why should public institutions pursue the goals of a private corporation? That is never considered. So you get the contracting out of welfare and employment services as an expression of this. The privatisation of the employment service in Australia exemplifies this stupidity.

What is efficiency?

Orthodox economists have a very narrow view of efficiency and this is tied to their belief that the only efficient and real economic activity comes from private enterprise. The private sector provides real jobs and the public sector "makes work". But this ignores the vital role that the public sector can play in providing activities that are essential to social efficiency, which is a much broader concept that that which applies to private profit units.

Essential public activities include:

- Public provision of health care, education, transport, childcare and the like are fundamental to our quality of life.

- Public provision of infrastructure is essential to private sector profitability.

The Market approach sees individuals in market terms only - as consumers or producers. The thing that is forgotten is that individuals also belong to communities and have the capacity to share values.

By pursuing The Market approach through deregulation and privatisation, allegedly chasing efficiency, the economic rationalists worsen unemployment. But, unemployment is the greatest inefficiency of them all. Work by myself and Martin Watts has computed the costs of unemployment. If the unemployment rate was to be lowered to 2 per cent, the gain in GDP would be $37.3 billion (at June 2000). Recently the Industry Commission estimated that the annual cost of Micro inefficiency was $22 billion (an overstatement). In other words, ignoring all the other costs of unemployment and just focusing on foregone output (and private profit opportunities), the losses from unemployment dwarf those from inefficiencies on the wharves, railyards, and the like - the so-called microeconomic inefficiencies. Why would a government worsen unemployment to chase second-order gains? A significant explanation would involve ideological zeal.

The same zeal extends to the decision to privatise as many public assets as the government can politically get away with. Privatisation has really nothing at all do to with efficiency. It is about redistributing the distributional claims on public assets. It has worsened the distribution of income. Since wages tend to be more equal in the public sector, privatisation is likely to skew the income distribution in the direction of greater inequality. Furthermore, while unions have lost ground in the private sector, they have generally made advances in organising public employees. Privatisation undermines these gains.

In general, the political uses of privatisation have compromised the so-called efficiency objectives. We have seen many examples of discount privatisations to ensure that a successful float ensues.

The budget deficit myth

There is an analogy drawn between household finance and the government budget in the orthodox economics literature. It is entirely fallacious at the Federal level and has been used to advance economic rationalism at the cost of the disadvantaged (and society in general).

Why are Government bonds-issued? The discussion that follows will consider Federal Government bond issues only. One of the most damaging analogies in economics is the supposed equivalence between the household budget and the government budget. The analogy is flawed at the most fundamental level. The household must work out the financing before it can spend. Whatever sources are available the household cannot spend first. Moreover, by definition a household must spend to survive. The government is totally the opposite. It spends first and does not have to worry about financing. The important difference is that the government spending is desired by the private sector because it brings with it the resources (fiat money) which the private sector requires to fulfill its legal taxation obligations. The household cannot impose any such obligations. The government has to spend to provide the money to the private sector to pay its taxes, to allow the private sector to save, and to maintain transaction balances. Taxation is the method by which the government transfers real resources from the private to the public sector. Any spending above taxation results in a budget deficit.

The logic according to those who draw the household analogy follows like this. Any excess in government spending over taxation receipts can be financed by borrowing from the public. Orthodox economists shun the use of non-interest bearing debt or currency as a means of financing budget deficits. They hold on to the discredited quantity theory of money which says that this method of finance will promote a rise in the money supply and inflation.

The government can borrow from the public by issuing interest-bearing bonds, which do not directly increase the money supply unless the central bank allows the commercial bank reserves to increase - this process is called accommodation. While this method of financing is not inflationary per se, it is alleged to cause interest rate rises and thus crowd-out private expenditure, which is sensitive to interest rates. The government borrowing increases the demand for loanable-funds and interest rates rise.

Like a household, the rising debt cannot be sustained indefinitely and so spending must be curbed and brought in line with the financial reality. Even Post-Keynesian economists hang on to the notion that there is some debt-to GDP ratio (and hence some implicit deficit-to-GDP ratio) that the economy can not go beyond. Capital markets will also determine the price of the debt.

As Randy Wray (1998: 75) says:

Governments are thus believed to be subject to market forces that determine the quantity of debt the government can issue as well as the price (interest rate) of the debt. If the domestic production will not take up all the debt, the government is forced to sell bonds in international markets. International markets might even force the government to borrow in a foreign currency (issue foreign-currency-denominated debt) if the country's finances are questionable. Indeed, the government may be forced to impose austerity on its population in order to placate internatinal markets before it will be able to sell bonds internationally.

The orthodox analysis is not only fallacious but it is also dangerous because it has resulted in periods of persistently high unemployment as governments around the world have been urged to curb their spending and live like a sensible household.

It is clear that the goverment can for a short period run a budget surplus but this is an unsustainable strategy because it causes deflationary income and balance sheet effects. We know that the private sector normally prefers to be net savers. Given this, sustained economic growth requires persistent government deficits to maintain demand. Importantly, the idea that governments can choose to finance its spending by taxation, bond-issues, or money-creation is completely misplaced. Government spending is always financed through creation of fiat money - rather than through tax revenues or bond sales. The basic role played by taxation is not to finance spending, but rather to provide an incentive for the private sector to accept government fiat money in exchange for real goods and services (which the government uses to fulfill its socio-economic policies).

Of crucial importance is that we understand why bonds are sold to the private sector. As we have seen the orthodox economists believe that debt is required to fund the deficit spending and to avoid printing money. Now what is wrong with this, seemingly intuitive reasoning that pervades conventional economic analysis? First, focus on the question of issuing debt following Government spending. Notice the way we express this. Debt issue after spending. The critics would turn this around and talk of debt financing implying you needed the borrowing prior to spending. It is this orthodox view which misunderstands the priority of spending and the subsequent role that the issue of securities plays in the financial markets. Debt issue does not serve to finance spending. Spending is whatever the Government chooses it to be plus automatic stabilisation. To understand this consider the operations of a fiat money system.

Fiat money is issued by the Reserve Bank of Australia (and typically by the central bank in other capitalist countries). It comprises notes and coins, which represent a non-convertible liability. This currency is called legal tender and ultimately is the only vehicle that is used to clear tax liabilities. It is used to convert bank liabilities and also to clear transactions between commercial banks and/or between banks and the central bank. It is always exchangeable for domestic production.

How does government spending take place? Randy Wray (1998: 77) says:

When a modern government spends, it issues a cheque drawn on the Treasury; its liabilities increase by the amount of the expenditure and its assets increase (in the case of a purchase) or some other liabilities are reduced (in the case of a social transfer, for example, social security payment liabilities are reduced by the amount of the social security cheques issued). The recipient of the Treasury cheque will almost certainly 'cash' the cheque at a bank; either the recipient will withdraw currency, or, more commonly, the recipient's bank account will be credited. In the latter case, bank reserves are credited by the Fed in the amount of the increase of the deposit account. For our purposes, it is not important to distinguish between the Fed's and the Treasury's balance sheet. The bank reserves carried on books as the bank's asset and as the Fed's liability are nothing less than a claim on government fiat money - at any time, the bank can convert these to coins or paper notes, or use them in payments to the state. When the recipient 'cashes' a Treasury cheque, a bank will convert reserves to currency - which is always supplied on demand by the Fed, which acts as the Treasury's 'bank', converting one kind of Treasury liability (a cheque written to the public) to another kind (coins or an IOU to the Fed, offset by Fed issuance of paper notes).

Clearly, the government spends on its program without any prior need for taxation or bond issuance. The sale of government debt is not essential for governments to spend beyond tax revenue. The role that bond issues play is totally removed from the orthodox financing view. Strictly speaking, bond issues are essential only to support the overnight interest rate that is exogenously set by the Reserve Bank. Deficit spending without Treasury bond sales would generate excess reserves in the banking system, so that government debt helps to maintain a positive overnight interest rate for private banks. The idea of crowding out in this real world environment is as meaningless as debates about the term maturity of the debt. Deficits add to the net disposable income of households in the economy and the income provides markets for private production. The higher demand stimulates investment that creates capacity as a legacy to the future. The higher is current demand, the higher is productive capacity in the future.

Nobel Prize winner Bill Vickrey (1996: 10) says, "Larger deficits, sufficient to recycle savings out of a growing GDP in excess of what can be recycled by profit-seeking investment, are not an economic sin but an economic necessity." As long as the monetary authorities provide financing for profitable investment opportunities that arise due to the higher spending, there can be no crowding out. In an endogenous money world, there can be no crowding out unless the monetary authority stops lending.

The recent Asian financial troubles and IMF intervention have once again given credence to the view that increasing levels of debt will eventually lead to lenders refusing to take up further public borrowing. Usually this is cast in terms of countries with low levels of capital that have major private debt denominated in a foreign currency which is used to finance imports. Crises occur when the export revenue, which services the debt, falls for one reason or another. But none of these countries would have any trouble issuing debt in its own currency.

Vickrey (1996, p 11) says, "In the case at hand the debt is intended to supply a domestic demand for assets denominated in the domestic currency, and in the absence of a norm such as a gold clause, there can be no question of the ability of the government to make payments when due, albeit possibly in a currency devalued by inflation. Nor can there be any question of balking by domestic lenders as long as the debt is limited to that needed to fill a gap created by an excess of private asset demand over private asset supply."

The point is clear. When fiat money is used, government spending increases reserves in the banking system. Taxation and borrowing drain the reserves. This gives the clue to the function of borrowing. A deficit generates a net build up in reserves in the banking system. The spending occurs and the private firms and individuals that sell goods and services to the government deposit the proceeds in the commercial banks, which build up reserves. Unless those reserves are drained from the system, they will earn a zero return. That is the role of the government bond issues is to give these returns a way to earn a non-zero rate of return.

To fine-tune this point further, the spending would still have occurred if there were no bond issues. The excess reserves would be held somewhere in the banking system earning zero return. If the Treasury offers too few or too many bonds relative to the holders of reserve balances at the Central Bank, the Central Banks "offsets" those operations to balance the system. In any case, the 'money' is in one account or another at the Central Bank. We then ask the question - why should government care if the holders of the excess balances chose the one that doesn't pay interest as opposed to the ones that do (buying bonds)? The answer is simple - they would be indifferent. to maintain demand for government fiat money. Finally, bond sales are used to drain excess reserves in order to maintain positive overnight lending interest rates, rather than to finance government deficits.

So to summarise, government bonds provide the financial system with an interest-bearing asset and allow banks with excess reserves an opportunity to earn above a zero return. Bond issues are part of monetary policy. If the fiscal spending has created excess reserves and there is downward pressure on the cash rate, then the Reserve Bank can sell bonds as a means of maintaining their cash rate goals. Spending adds to reserves while taxes and bond sales drain reserves. The latter are considered to be part of the Reserve Bank reserve maintenance operations and nothing much\ at all to do with fiscal policy.

Corporate welfare

It is interesting to note in a time when welfare assistance to the most disadvantaged is being attacked corporate welfare is booming. While recipients of individual welfare payments are being forced under the guise of Mutual Obligation to be more accountable, the corporate sector is largely unaccountable for the significant handouts they receive after lobbying the government. These payments are completely at odds with the free market model and lead to the conclusion that the implementation of, allegedly, market-based reforms are inconsistent and ideologically driven.

A recent case study is the Federal Government's heavy subsidies to the private health insurance providers. This is the ultimate hypocrisy of the Market lobby. The market sentiment of consumers was clear - the products offered by the private health insurers were inferior. Either the quality had to rise or the price fall. That is the logic of the market. But the Government chose instead to use tax revenue to underwrite the profit margin of inferior (judged in the market) products.

Blaming the victim

The Market approach has also allowed the Government and others who support the wholesale contraction of the public sector and the Welfare State to focus attention of the victims of the policy changes rather than the causes. We now have offensive concepts and words like mutual obligation, dole bludgers, welfare frauds, single mothers, aboriginals and the wheel, and the like - used to divide and isolate disadvantaged persons in our community.

The contribution of economists here has been to blame the individual and the manifestation has been the plethora of training schemes, which have been mostly wasteful.

Loss of public services and goods

The logic of The Market has been applied to ever-increasing areas of our lives. This is despite the criticism that public service should not have to meet a private profit test. Some notable aspects of the public sector cutbacks have been the reduction in support to research and development (for example, CSIRO), the low investment in AARNET (Australia is one of the lowest investors in national network infrastructure in the OECD), and the pressures that have been placed on the tertiary education sector. The myopia of these policy changes is palpable. In the context of the debate about whether we can become a clever new economy, they are suicidal. The Government aided and abetted by economic rationalist economists have sown the seeds for mediocrity in this country.

The global divide

I now want to say a few things about the global situation and consider financial and trade deregulation, the debt crises, free trade and the role of the IMF and the World Trade Organisation.

The Market lobby has also overseen the deregulation of global trade and finance. Once again the free market rhetoric ignored the reality. Large hedge funds can, for example, move a complete market. There is ample evidence of market-making behaviour. Liberalisation has led to massive over-investment in less developed economies. Highly levered speculative investment has driven out safer equity investment in many economies. This has been driven by the existence of moral hazard which again violates the free market rhetoric. In Asia, for example, the over-investment was concentrated on land and so the prices rose. The Asian economies experienced a noticeable boom-bust cycle not only in investment but also or even especially in asset prices. These assets were in imperfectly elastic supply. The financial intermediaries were able to borrow at world interest rates because they were perceived as being guaranteed. The damage done to Asian economies in recent years has been huge. It is the disadvantaged that bear the brunt.

Not only have the speculators caused damage via the exchange rate but the liberalisation of credit has also led to a debt crisis. A vicious circle has developed which has made the poor poorer than they have ever been. The vicious circle of debt is captured by the following diagram:

What about free trade. There have been significant public debates about globalisation the World Trade Organisation, the World Economic Forum and the like the recent years. The proponents of The Market approach extol the virtues of free trade without telling us that there is very little free trade - by that I mean that countries trade on level playing fields. If trade was free and products were produced in circumstances that we all found acceptable then we would all benefit. Unfortunately, this is far from the reality that\ we face today. Globalisation is a most misunderstood phenomenon. It is not inevitable - only age seems to be inevitable. The image tha globalisation is a purely technological issue that pervades national and social boundaries is simply wrong. Globalisation is in one sense just the liberalisation of investment, capital and trade flows. Note the term liberalisation. We have to ask who did the liberalising. The process of globalisation can be controlled by the same bodies that allowed it to go out of control - governments and multi-government international bodies.

One of the biggest reasons that globalisation has had such devastating effects on communities, children, the environment is that is has occurred under the guidance of the World Trade Organisation. The goal of the WTO is to deregulate international trade. WTO Agreements represent little more than extensive lists of policies, laws and regulations that governments cannot establish. The agenda of the WTO prioritises the privatisation of education, health, welfare, social housing, and transport. Some of these prohibit measures intended to regulate international commerce (controls on endangered species trade or bans on tropical timber imports). But many others prohibit regulations that might only indirectly influence trade such as recycling requirements, energy efficiency standards or food safety regulations. The WTO has extended the reach of trade rules into every sphere of economic activity. Previously, it considered only tariff constraints in trade in its former guise as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Under the aegis of the World Trade Organisation it extended its ambit into what it calls non tariff barriers to trade - essentially any national or local protective legislation that might be construed as impacting trade. It now attacks any efforts to limit trade due to its labor implications, ecology implications, social or cultural implications, or development implications

Historically trade agreements were concerned with the trade of goods across international borders. But the WTO now considers investment measures, intellectual property rights, domestic regulations of all kinds, and services. The hypocrasy comes when you see that the WTO will enforce harsh penalties when the interests of investors and capital is threatened. For example, when workers are being forced to work in conditions that violate human rights (and international labour agreements and laws), the WTO says there is nothing it can do. But if the same workers were involved in producing pirate media (which threatens a multinational corporations copyright) the WTO will impose sanctions in order to protect the intellectual property of the corporation.

Many have described WTO rules as representing little more than an international bill of rights for transnational corporations. There is no public input or accountability. Most of us would have supported the trade sanctions that led to the release from prison of Nelson Mandela and the breakdown of the apartheid system in South Africa. Under current WTO rules, this type of international action would be impossible.

Consider the following series of questions:

- How many of us would like our children to be exploited in sweatshops at the age of 13 and have irreparable physical damage by the age of 18?

- How many women here would think it reasonable to have to sign "non-pregnancy" conditions before they were hired?

- How many would think it reasonable to be denied the right to bargain over wages in a union?

- How many would think it reasonable to work for near starvation wages while the product was sold for many times the cost in international markets?

I suspect no-one in Australia would be affirmative for any of the questions. So the next question is: How many of us have bought Nike products?

The sponsors of Australian Olympic team have appalling labour practices in Indonesia and Vietnam. They are not alone. Many multinational corporations operating under the protection of the WTO produce products in conditions which blatantly disregard for human rights. Why do they survive? They survice because we purchase their products. In the context of the market, there is some power for each of us. If we stop buying products produced by companies under conditions we consider unacceptable then the trade will stop.

The following list outlines 10 reasons to abolish the WTO:

The alternative is to regulate global corporations and markets so that local communities can control their own economic lives. We need to promote trade that:

- Reduces the threat of financial crises.

- Increases the operations of democracy at community levels right up to multilateral organisations at the global level.

- Sustains the sanctity of human rights.

- Is environmentally sustainable.

- Enriches the most disadvantaged.

The type of policies that need to be considered include the encouragement of domestic economic growth and development rather than impose domestic austerity in favour of cash-crop, export-led growth; the taxation of speculative capital flows, and the establishment of standards to regulate of financial institutions by national and international regulatory authorities.

The path to full employment

I want to conclude by focussing on what I believe is the major evil that has arisen in this period of economic rationalism - persistently high unemployment. We need to redefine the mean-spirited Mutual Obligation (that reflects Market-ethics) to embrace a Job Guarantee (that reflects shared values).

It is interesting to note that a number of economies maintained low unemployment levels throughout the 1970s, 1980s and on (Austria, Finland, Japan, Norway, Switzerland are examples). The reason why is simple. They did not adopt economic rationalism and maintained an emphasis on being societies and communities. They maintained shared values.

Their governments (or a sector) maintained a role as employer of the last resort. It comes at a cost which has been shared by all. In Australia, during the 1950s and 1960s, the public sector played this role. Full employment was maintained that way.

Persistent mass unemployment has arisen as government?s have bailed out of their responsibility to act as an employer of the last resort. Persistent mass unemployment occurs when the budget deficit is too low. What is required is a restoration of the collective will and a downplaying of individual greed. There is such a thing as society. The welfare of society is not maximised by the blind pursuit of individual ambition. We have to stop blaming the victim.

The Olympic Games

We have all been feeling good about the Olympics. I contend that we have been feeling the glow of shared values. We rediscovered the collective will. Despite having placed our faith in the market for several years, the Olympics showed us the effectiveness of the state in delivering goods and services and allocating resources in a socially efficient manner. Much of the organisation reflected planned outcomes aimed at delivering public services rather than allocations driven by expectations of a market return.

The Job Guarantee

- What is the Job Guarantee?

- How it would be combined with social wage measures and the introduction of a negative income tax scheme.

- Wouldn't it cost too much? Watts and Mitchell (2000a) estimate it to cost $7.52 billion.

- Wouldn't it be inflationary? The answer is that the design of the Job Guarantee proposed by the Centre has the combined feature of restoring full employment and maintaining price stability. (c) Wouldn?t it be just useless make work? There is a plethora of jobs that can be created to enhance community welfare and reduce environmental degradation. The private sector would never create these types of jobs because they would not generate profits.

- Wouldn't it just be Workfare? Definitely not. Workfare is a mean-spirited attempt to force people to pay for being disadvantaged. The Job Guarantee ensures people have access to well-paid positions on a permanent basis if needed, which attract the usual benefits of employment (leave, superannuation, and the like).

- Wouldn't it damage the current account? With lower unemployment, we would expect higher imports. But there is a flexible exchange system which over time adjusts to that. It is rather repugnant to argue that we have to maintain high unemployment and concentrate the job losses among the least advantaged in our community just so that those in employment can consume imported goods. If the lower exchange rate is a problem then we have to impose higher taxes on those with higher incomes as well as introducing the Job Guarantee to maintain whatever import spending level is desirable.

I leave you on a quote from the founding father of the American social security system, Arthur Altmeyer who in 1968 said:

What motivates people and leads them to high endeavour is not fear but hope

The current system emphasising the mutual obligation and the market is based on engendering fear and insecurity into the lives of people. It is bound to fail. To motivate people you have to give them opportunities and hope. Mutual obligation has to involve the responsibility of the government to provide sufficient work for all.